Author: Marco Vivolo

Trainee clinical psychologist currently on an international placement at Thrive Well

University of East Anglia, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Trauma and adversity are conceptually similar terms often associated in research, particularly within the context of resilience and post-traumatic growth. However, differentiating them can be helpful to isolate specific conceptualisations that can contribute to widen our understanding of the impact of trauma and trauma-informed care (TIC) more generally.

What is trauma and how is it differentiated from an adverse experience?

Adversity is a generic concept that involves the experience of challenging events, environments and circumstances, also from a developmental perspective (i.e., the challenges a child might experience growing up), while trauma is a potential consequence of these adverse experiences, often with last-longing effects. Therefore, trauma normally requires psychological and/or other interventions to promote recovery, growth and resilience, as it can have a significant impact on the person’s life and day-to-day functioning (e.g., physical, emotional, behavioural, interpersonal difficulties).

Why is an understanding of trauma increasingly important when providing mental health support?

Understanding trauma can help services shape their care in compassionate and caring ways, as this kind of care focusses on the exploration of difficult and challenging past experiences and how they currently impact the individual, rather than simply focussing on observable and noticeable symptoms. Understanding trauma normalises and de-shames the person’s difficulties as they are seen as part of a process that has developed over time, rather than the person’s own fault, flaws or shortcomings (“the things that have happened to you are not your fault”, in the words of Paul Gilbert, founder of Compassion-Focussed Therapy). In terms of prevention, understanding the links between trauma and social/physical health/psychological wellbeing is key as it can help services identify people who are at higher risk of developing physical health and psychological problems (e.g., severe and enduring mental health problems). Research has highlighted that ACEs are linked to a higher likelihood to experience IHD, cancer, COPD, stroke, diabetes, obesity, smoking, substance misuse problems, STD’s, attempting suicide and depression (Felitti, 1998).

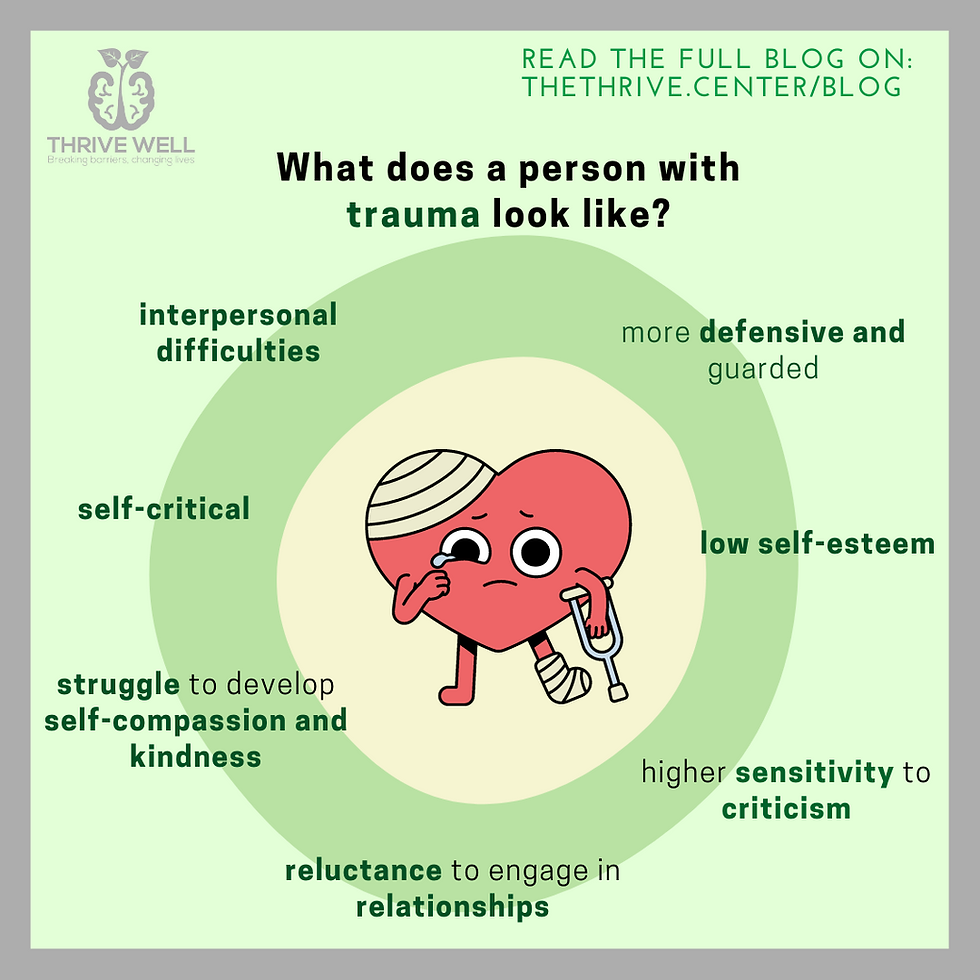

What does a person with trauma look like, (e.g., what kinds of behaviour or thought patterns do they exhibit)?

Depending on the type of trauma, people can develop a range of difficulties and mental health challenges. Self-esteem is often impacted, there might be emotional avoidance, or interpersonal difficulties, such as a reluctance to engage in relationships as they might be perceived as damaging or dangerous. People who experience trauma might be self-critical and struggle to develop self-compassion and kindness, or think that they are not good enough. They might also avoid things, such as social contact. Some people might just develop a higher sensitivity to criticism, making them more defensive, guarded or on edge. It is also important to remember that traumatic experiences and related difficulties are idiosyncratic and unique to the individual, so while identifying some common patterns is helpful, people experience their difficulties in different ways.

How different is childhood trauma from trauma sustained as an adult, and why so?

Developmental/childhood trauma impacts specific areas of the brain as they are not fully developed yet. There is evidence to show that early trauma affects the brain in significant ways, such as in terms of serotonin levels (De Bellis & Zisk, 2016), the ability to regulate emotions and impairing the ability to recall positive memories over negative ones (Bremner, 2006).

How does a clinician determine whether someone suffers from trauma, and how does it influence how a person is treated and supported?

Developing a longitudinal and developmental understanding of one’s difficulties can help clinicians understand where their difficulties stem from, rather than focussing on visible “symptoms”. Collaboratively developing a patient-centred formulation can help both clients and clinicians to gain an insight into early traumatic experiences that continue to affect the individual. This, in turn, can enable clinicians to recognise unhelpful cognitive and behavioural patterns, while ensuring that the client’s difficulties are normalised and validated.

Relevant psychometric tools (e.g., ACE questionnaire) can be employed to inform this process and develop a meaningful narrative.

What are some common misconceptions of what is trauma?

Trauma can be defined as a perceived life-threatening experience (i.e., PTSD). While trauma can be described in such a way, it is not necessarily about life-threatening experiences (continuous, systematic emotional neglect, for example, can be classed as trauma). Therefore, trauma is not necessarily a life-changing event, such as a car accident or a major physical injury, but can also be experienced through repeated exposure to neglectful and abusive environments, even if these are not perceived as life-threatening.

How did you personally become more interested/aware of trauma-informed care and making it part of the focus for Thrive Well?

Personally, I became aware of TIC while working in the UK (both prior to and during clinical training), as I was interested in developing a greater understanding of clients’ difficulties and their meaning, rather than solely focussing on diagnoses and symptoms. The work carried out by Lucy Johnstone (Power Threat Meaning Framework) and Paul Gilbert (founder of CFT) definitely inspired me, prompting me to adopt more transdiagnostic therapeutic approaches.

Can you share any personal experiences on how TIC is applied in a therapy/clinical setting?

Examples of TIC in clinical practice include transdiagnostic approaches to mental health care, but also supporting other professionals (e.g., social workers, nurses, doctors, care coordinators, etc.) in formulating clients’ challenges in a trauma-informed way. This can take the form of consultation, group/peer support and even supervising other professionals as they carry out psychological interventions. It is also important to recognise how trauma-related patterns impact the therapeutic relationship, as they are often likely to present themselves in therapy. More generally, an MDT (multi-disciplinary team) approach is best placed to meet the needs of clients who experienced trauma, as it offers a more comprehensive framework in which care can be provided, addressing a wider range of issues (e.g., social care, employment support, medical treatment, recovery programmes, etc.).

What does healing look like for someone with trauma?

Recovering from trauma is definitely possible for clients and often involves exposure to difficult situations that are perceived as threatening or challenging. It implies reclaiming their lives and being able to go back to some of the activities they used to enjoy. Recovery from trauma is often associated with an improvement in their day-to-day functioning and involves resilience and growth. It can restore the client’s “baseline” level of functioning and even improve it.

How can we create a more empathetic community as a whole for people in trauma (e.g., in settings like schools, workplaces, at home)?

By promoting awareness of TIC and what trauma involves, but also normalising trauma to de-shame and combat stigma. Schools, workplaces, community centres and other community-based organisations, including religious ones, should be offered training, psychoeducation and support to better understand trauma and provide a safe space for people to talk about it. This is key and particularly important for children and young people, so that they can get the support they need early in the process. Liaising with local organisations, charities and institutions can help build more effective networks to talk about TIC. This shift will inevitably have cultural implications, which are just as important to acknowledge.

コメント